![Steve Diskin Steve Diskin]() Steve Diskin

Steve Diskin

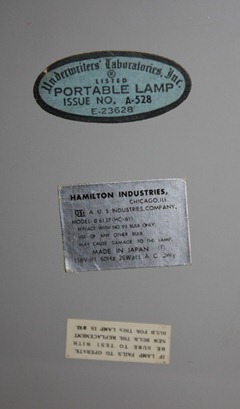

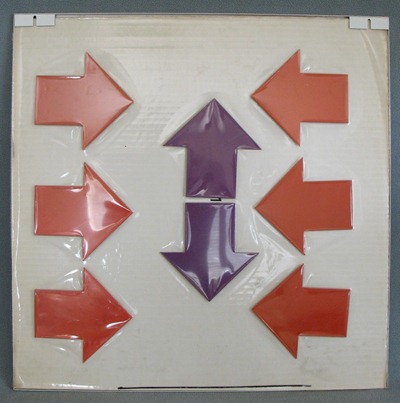

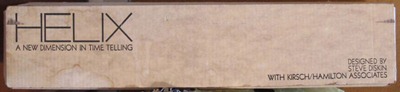

Kirsch/Hamilton and Associates, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1979

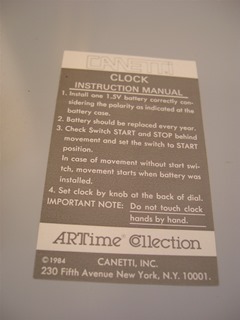

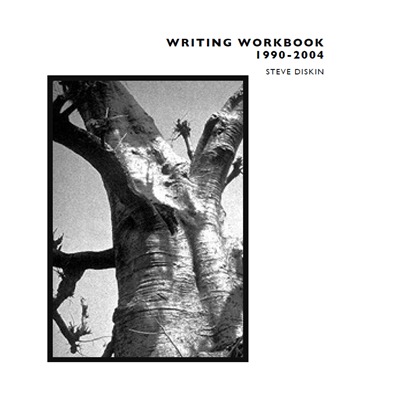

Writing Workbook 1990-2004 by Steve Diskin is a collection of essays. The selection entitled “Sentimental Mass Production” from 1995 is Diskin’s reflection on the Helix clock, from its emergence as a concept to its execution as a design object. Click the link above or the cover below to read the entire book. Click for a brief biography of Steve Diskin.

![Writing Workbook 1990-2004 by Steve Diskin, cover Writing Workbook 1990-2004 by Steve Diskin, cover]()

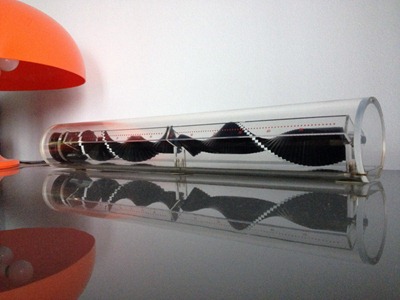

The lecture and essay have been described as “an emotional introduction to industrial design from an architect who didn’t know what he was doing.” I think the journey, and the results, turned out wonderfully. The Helix clock, and later designs for Tik-Tek Engineering, represent stunning conjunctions of timepiece and design object.

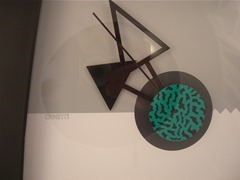

![The Helix clock by Steve Diskin for Kirsh/Hamilton and Associates, Inc. (1979) The Helix clock by Steve Diskin for Kirsh/Hamilton and Associates, Inc. (1979)]()

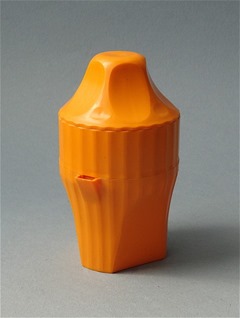

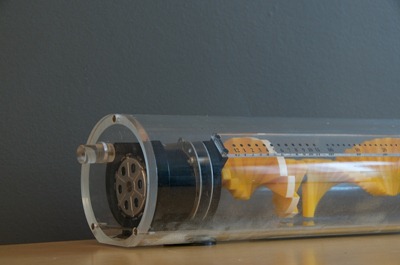

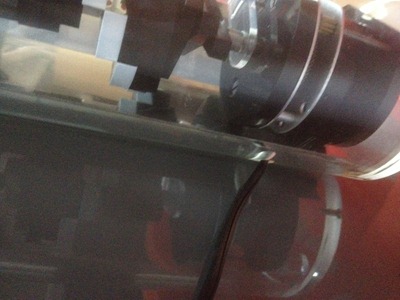

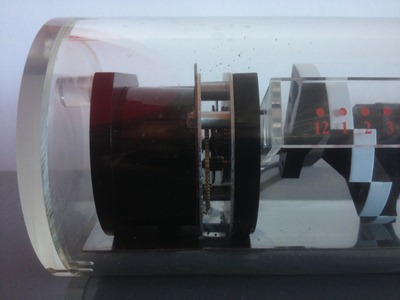

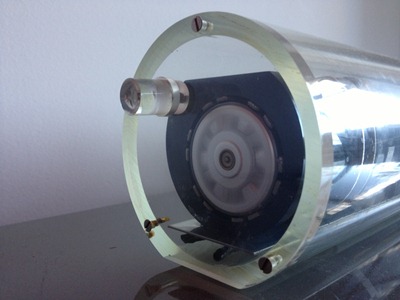

The Helix clock by Steve Diskin for Kirsch/Hamilton and Associates, Inc. (1979).

Sentimental Mass Production (1995)

I have at some point considered the literary notion that design is a narrative process, with designers as authors of the great stories linking objects and human beings. These are the stories of environment, character, poetry and time, sentimental wanderings of thought and form where inanimate and animate objects are interwoven. A parallel reality of environment, character, poetry and time enlivens the universe of objects with their own lyrical biology and structure. In this world a man and his work are not separated; in the special world of design, you are what you make. This is how I got started in industrial design.

In the chain of being linking sub-atomic particles to mankind, there is something missing: the object....extension of man, elusive artifact of evolution!! Moments like the Voyage of the Beagle or Haeckel’s Expedition in search of little geodesic radiolaria, or a designer making a product, are Darwinian links in a greater chain of being. Objects come alive, children of the designer-mind, in time and in space as evidence of our existence, in many cases long after we are gone. Just as DNA has a language, the mass-produced object, by its dissemination throughout the world, also becomes a powerful device for communication. This dynamic quality of the secret life of objects vibrates within objects large and small: the clock on the wall is a blinking eye in a factory.

Take a look at Sapper’s Tizio, the flamingo of light, or an innocent paper clip, a snake; the walrus has the repose of the exalted goddess of all vehicles, the Citroën DS. These objects, these beings, more than remind of us animate forms; they indeed are animate forms.

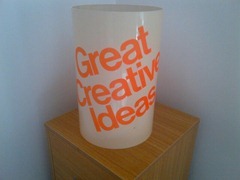

Far from that operating room where design lies on the table for surgery, where men in white try to solve the technical problems which they themselves conceive, I’m thinking that the vibrant heart of design lies elsewhere, in the making of objects. This thought originates in the mind of a designer as the deep need for a conversation with civilization, the desire to say something....and it often starts with a BIG IDEA.

My idea arrived in 1976. While I was in Japan working as an architect, life was hard. (13A) We worked very long hours, but sometimes there were great rewards. You will, I think, recognize another exalted goddess, the Citroën of human beings. (13B) At a certain point, I suddenly had a hunger for a really small and personal project, so

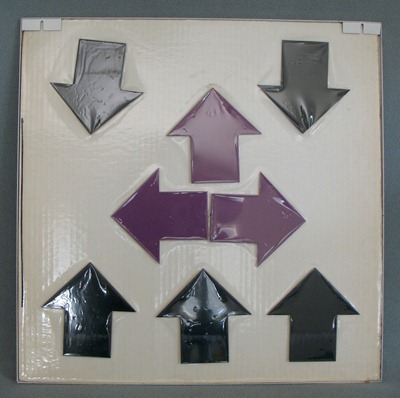

I decided to consider a different way of telling time! I found that after months in a strange land, one begins to absorb cultural information very rapidly, out of a hunger for understanding. In Tokyo, the atmosphere crackled with architecture, symbols, society, objects, as well as a different relationship with time. A culture where natural disasters formed the shape of the city (and where until 1873 time was measured by hours which varied in length from day to day, through the seasons of expanding and contracting daylight), cannot fail to give a designer certain ideas.

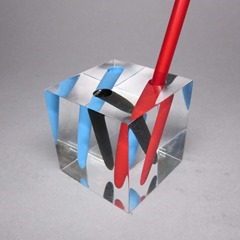

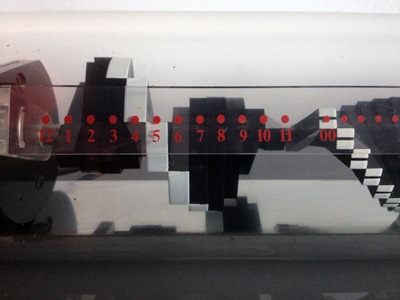

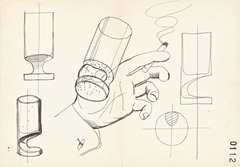

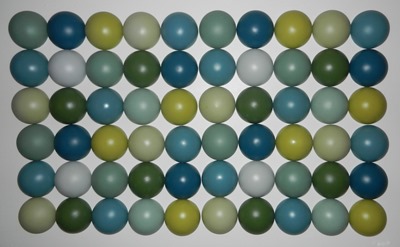

I had in mind a “color clock”, a cylinder of many illuminated bands, with a helical mechanism inside to sequence the lights with an ordinary motor. This prototype in my mind stimulated the further thought that the mechanism itself might be an interesting sculptural “thing”, and that most people wouldn’t bother about “blue minutes after pink o’clock”, or being “yellow minutes late for a meeting”. (In parentheses, I also realized that an object can force users into learning a different language and that this demand easily makes enemies of consumers.)

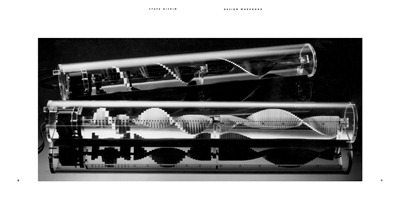

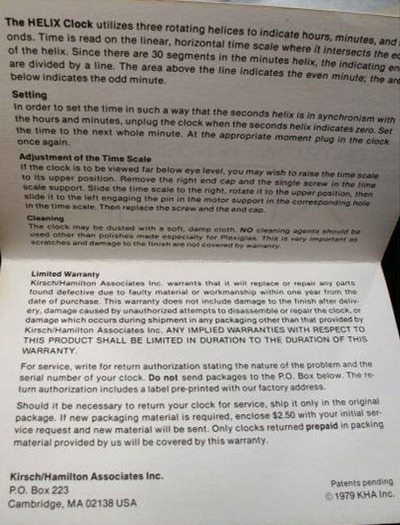

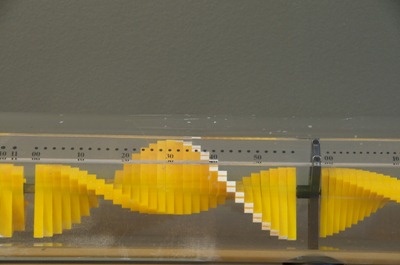

So, a helical clock was born. Named Helix, it was really just a machine for spinning rotary motion into linear motion, a Nautilus chronometer, sea-shell of time, a wheel rolling down the space-time continuum, a well behaved spiral advancing forever, resetting itself with periodic certainty, a solidly mathematical spiral staircase to infinity.

As I have said: far from the world of “problem solving as we know it”, I have found that the heart of design lies in the lyrical and sometimes capricious nature of objects. Design ideas form a rich soup, with ingredients bubbling to the surface at random from the invisible depths at the bottom of the pot where they can burn and be destroyed if the flame is too high, or take on the color of the surrounding broth, the ooze in which ideas can easily disappear. The process, nevertheless, is frequently nourishing; but once in a while one gets indigestion, or worse, food poisoning.

The soup in question here is a helical soup. In this pot are a year’s worth of prototypes, and the steep learning curve of a new field with its own language and materials; but I was still guided by the lyrical impulse, a kind of childlike wonder about objects and their making. This period included flirtation with expressive form, materializing as a celebration of seconds. Hours move very slowly in a clock, measuring time in a very unrewarding way. I wanted more.... more drama, more action, so I made three helical rotors, and made the one which shows seconds very long, in sixty discreet segments, and then accentuated it with a polished mirror base which reflected the sensuous rhythm of the passage of time.

I decided to show this prototype to another human being. My friend saw this funny machine, actually liked it and said he would like to buy one. (This is called “market research”, by the way).

My studio was in my mother’s garage, and I say “studio” because of the romance of this word. A studio can be anywhere, or anything...it is a special architecture of the mind. I showed Helix to a university professor of business. Six students in his class signed up to help me research the feasibility of bringing the Helix to market. “Market” is indeed a romantic, expressive institution. It is, I can tell you, “the market” which animates products; in the market the designer can hear the sweet songs of fame, fortune, and affection for one’s work. I loved the smooth sound of the word “entrepreneur”, and remember the pride of anticipated ownership of this title; but my real dream was a chimney, the heavy cloud of the particles of object-making, the industrial cigar, belching evidence into the atmosphere over my fantasy factory, proclaiming in the most lyrical words of all: MASS PRODUCTION!!!!!

Now let me give you an observation: I believe that all objects are like penguins. Frolicking on the assembly line, anticipating the mating ritual with other parts, totally comfortable where its cold, at home on land or at sea; objects are just like penguins struggling for the shore .....longing to swim and play. For objects, that Great Ocean is of course, the Sea of Commerce.

So here were six students eager to put me in business. We photographed the prototypes, visited retail stores, interviewed owners, tried to price parts, learned of exotic processes and materials, and went to trade shows. I laugh now, but these were ardent efforts, by new entrepreneurs wearing fictional three piece suits, smoking fictional cigars, with light bulbs and dreams in their heads, inventing grand plans.

We would become mass producers, another cell in the great chain of being: makers of objects. But then I called a phone number in Boston. I had learned of a little two-man company, (an architect and a physicist who lived the dream of cigars and light bulbs), mass producers of clocks which employed polarized filters to make the face change color as time passed. (Sound familiar? Ideas, like twins, always come in pairs.)

I took the red eye. They wanted to see the Helix clock. The great moment of this visit was the factory. Machines everywhere, precision machines, numerically controlled lathes and mills, grinders and drill presses, hand tools and testing racks, strange-looking fixtures and a definite mood that here was a place where man and machine were equals.

Here was the heart of industrial design. This was an alchemical place where ideas transmuted into objects, like lead into gold, a place where sea lions would play, where products would jump from their boxes, dancing through the night to the tunes of an orchestra of cast aluminum instruments or a mighty pipe organ, let’s say a pipe organ of acrylic tube, of every diameter and wall thickness. This was a place I wanted to be.......

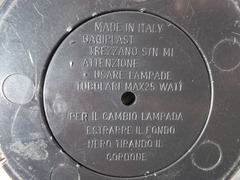

We talked of licensing, production costs, sales, materials, patents and royalties. We decided to call the lawyers: it was time to make a deal. It became a 22 -page agreement. It went like this...... “In consideration of one dollar, paid by the Licensee to the Licensor, the receipt of which is herein acknowledged, the parties agree as follows”: Licensee shall place on each of the Licensed products the following acknowledgement: “designed by Steve Diskin” in a location on such Licensed Product that is visible to the naked eye when such a product is in ordinary use.” Sea lions on rocks by the sea barked loudly: The objects were laughing, so were the lawyers.

Parts for five prototypes were made on a pantograph mill and carefully assembled into the finished clock. 102 little handmade parts. Revolution in the streets of objects!! The solution would come from a farm in Connecticut, where a small injection molding company offered to make these little segments. Cows stuck their heads through the window and mooed. Parts began to fill a cardboard box. Registration pins and holes in each part made assembly much easier. Tight angular tolerances had to be maintained.....sixty segments to make one 360 degree revolution, not 361. We were nervous. The cows were nervous. We had to decide what color to make these parts. Black and yellow were proposed. Then I said, “chrome.” Silence. Then enthusiasm!

The physicist took us to MIT and put one of the rotors under a huge bell jar in a lab, and vaporized a little piece of aluminum in an exquisite, airless void. The pump burbled, the aluminum was consumed. Scientists laughed.

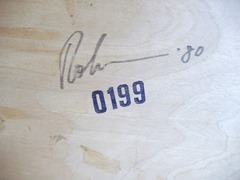

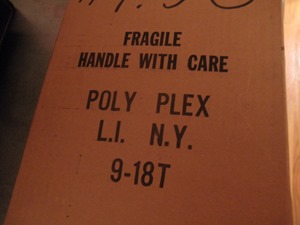

Chrome, black and yellow production prototypes went to the LA gift show. Orders were taken. Helix would be shipped in time for Christmas! I spent weeks in Boston at the factory, designing fixtures for hot stamping the rotors, milling endcaps, breathing the heady vapors in the factory, the smell of incipient mass production. Labels were applied to the newborn clocks: “designed by Steve Diskin” would indeed be visible to the naked eye when the product was in normal use. The first unit went to Beverly Hills. I waited clandestinely in the store listening for comments. “I hate this thing,” a mother told her 12-year old son, who openly coveted serial number 1, “It makes me so mad......” A week later I heard from the owner of the store that number 1 was sold.... and to a noted luminary at that!.... Stevie Wonder. Who says that there is no poetry in mass production.!!!

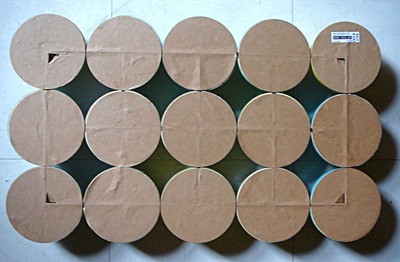

Shipping started, but then disaster struck. Inadequate packaging failed to protect the object inside. Gravity, inertia and momentum, intersected; matter and energy collided full force. A Helix in a box went to the testing laboratory. It sustained nine g’s as it hit the floor. This at last forced into existence a container which swaddled the newborn in an additional cocoon of plastic bubbles.

“Shipping”: it’s the third panel in a medieval triptych of object-making, hinged to the iconic representations of “Sales” and “Production”. Shipping is descended from the altar of the prototype (through the fury of mass production, the wild meiosis of subassemblies and parts), and is always preceded by a period of calm when only the rustle of paper can be heard, backstage at the drama of shipping, directed by the numerology of purchase orders, invoices and packing slips----the chronicles of product lives. Designer makers look on wistfully as friendly birds leave the nest. Ultimately, shipping is a form of flight, in all the meanings of the word.

In the mean time, Helix appeared in stores, catalogs, magazines, and newspapers. After a year, difficulties in production were gradually resolved. And at this moment the company was sold. The new owners weren’t cigar smoking light-bulb heads at all, but decaffeinated and pasteurized, gold-chained businessmen. They saw balance sheets where smokestacks should have been. The music of the factory became silence. It would be a matter of time, so to speak, before the Licensor and the Licensee would part company. Fewer than 1000 clocks would be sold.

There would also be no going back. In 1980 I made another decision. I would be a designer-maker, a manufacturer. Helix had been my rite of passage into the mysteries of industrial design and now I can barely remember life before ID. It’s like a pianist trying to remember the feeling of not being able to read music. In a 40 square meter studio-factory, we subsequently produced thousands of new clocks, simpler clocks, but nevertheless proudly displaying the label: “designed by Steve Diskin” and visible to the naked eye when the product was in normal use. For five years, objects danced in the night on the sixth-floor terrace of an old office building in Los Angeles.

In small scale production, a designer-maker learns to distinguish the inevitable defects which make each object minutely different from the rest. Seeing so many of these little objects side by side while they were in the studio, I got to know the quirks of each one as if by name. And I ask myself: Is there any doubt that objects and designers commune at the workbench, the altar of creativity? Whenever I see a product with a scratch or a screw missing or a part which doesn’t fit, rather than getting angry, I am reminded of mass production, and personality, environment, poetry, character and time. I love old products, discontinued products, defective products and, naturally, beautiful new products.

When I would make prototypes, and the studio would have already become a complete mess from the cutting, drilling, and sanding and painting of parts, I would always clear a sacred area on the workbench for a bit of soft cloth to make a ceremonial hearth for the rite of final assembly. With the sweet smell of paint (especially flat black) infusing the air in the studio, there would be the perfect parts, waiting. You hold a screwdriver reverentially when you assemble a prototype and there is a glowing halo when the job is done. This is standard procedure at the altar of creativity.

But the real pulpit of object-making is in the factory. It was a moment of true serenity in the quality control room at a certain metal stamping plant as I, a designer admitted to the inner circle, and fabricator, micrometer in hand, admired the first article: production piece number one. The fabricator knew and admired the careful work of the designer and the designer respected the capability and experience of the fabricator and both knew that the other knew. Both stood here on the same sacred spot. The altar demands recognition, and people who understand the life of objects know this. People who understand objects know that a car always runs better after it’s washed. These people also understand computers and know that the battle at the man-machine interface involves not so much the humanization of machinery with friendlier software, but more the convincing of human beings that it’s OK to coexist with objects.

What does all this mean? A corollary of the widely heard idea that small is beautiful is that small efforts are also beautiful. The executives of General Motors or Hitachi, like the owner of a one-man shop, have had ethereal dreams of the smokestacks of production, they feel the the primitive urges of the making of objects, they agonize over the minute technical details of finance and design, and watch with complex emotion as shipping disseminates the dream to the consuming populace. This is the life of the designer-maker.

Finally, Nature will resist a break in evolution, through the mechanism of genetic destiny and force of the environment. The persistence of objects, and of the humans who design them, is given. I, in my own small corner of design, also know that I am not alone in what I think and do. Sea lions play, and trees will grow happily where the conditions of humidity are hospitable; human beings dream, and billions and billions of the products we have inserted into a very interesting ecosystem of objects, will dance the night away under beautiful halogen suns, in factories real and imagined, throughout the entire universe.

Reference

Diskin, Steve. Writing Workbook 1990-2004. Czech Republic: 1990-2004. 44-51. eBook. http://home.earthlink.net/~stevediskin/writing.pdf.

see “Sentimental Mass Production” Dom & Wnetrze,

Warsaw, 1992, Innovation Magazine, 1995.